Introduction

Hello everyone, and welcome back to my blog. In this crash course we will be looking at one of the more popular and well known containerization technologies on the market, Docker. Now, this is going to be a longer, in-depth posts, so if that isn’t your thing, you might want checkout my Docker CLI Cheatsheet. However, if you like to get a better understanding of Docker and how it works, then you came to the right place. All this posts assumes is that you have docker installed on your PC. With that said, let’s begin.

What is Docker?

Docker is a tool for running applications in isolated environments, otherwise known as a container.

Now if you have been in tech for awhile, you might be thinking, Wait, isn’t that just a VM? and in any other circumstance you would be correct. However, Docker and other containers are different from VMs as they:

- Run containers in seconds instead of minutes

- Have less resources, resulting in less disk space usage

- Use less memory

- And, do not need the overhead of a full OS

This means that spinning up a docker container is extremely quick as it doesn’t load anything that is not needed. Another added benefit of docker is that since the application runs in the same environment, it will work on any machine that can run docker. If the application runs on your Mac or Windows PC it will run on your Linux server just the same. It is because of this that docker and other containerization technologies are gaining wide spread support in businesses across the board.

Containers vs. Virtual Machines

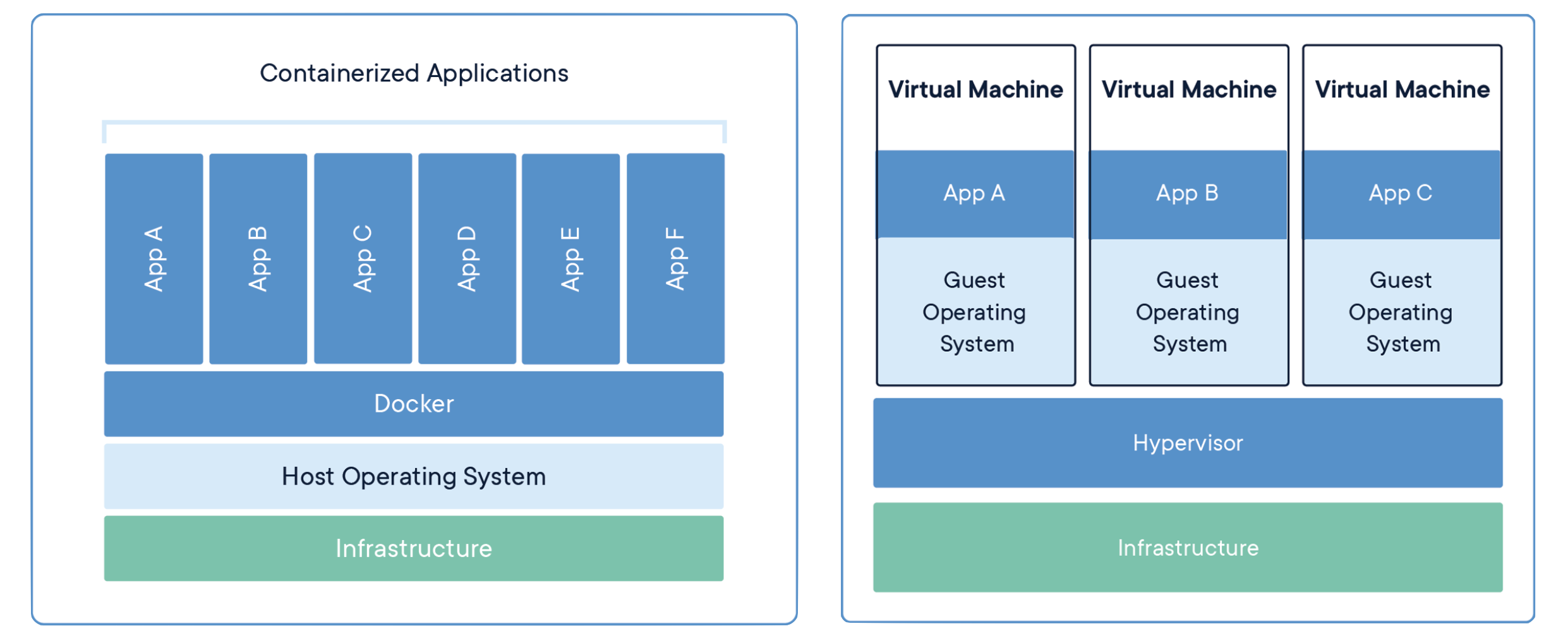

To go a bit deeper, lets examine containers and virtual machines a little bit more. Let’s begin by defining what a container is and what a virtual machine is.

Containers are an abstraction at the app layer that packages code and dependencies together. Multiple containers can run on the same machine and share the OS kernel with other containers, each running as isolated processes in user space.

Virtual machines (VMs) are an abstraction of physical hardware turning one server into many servers. The hypervisor allows multiple VMs to run on a single machine. Each VM includes a full copy of an operating system, the application, necessary binaries and libraries - taking up tens of GBs. VMs can also be slow to boot.

To make that a little bit easier to understand, lets look at Figure 1

Here you can see perfectly why containers are such a useful application in comparison to VMs. On the left-hand side, you see a system for containerized applications. The only overhead of that system is docker. On the right-hand side, you see a system for VMs. That system’s overhead is not only the hypervisor, but also each VMs’ Guest OS. As defined prior, this can be extremely wasteful in terms of system resources as each VM contains possibly unneeded items. The way docker solved this was by running applications in pre-built abstractions known as images.

Getting Our Hands Dirty

Now that we have some basic information down, lets start actually using docker. To start, lets mess with some images, specifically in this case the nginx image.

Docker Images

An image is a template for creating a sandboxed environment for solely running your application

To see an image in action, run this command:

docker pull nginx && docker run -d -p 8080:80 nginx:latest

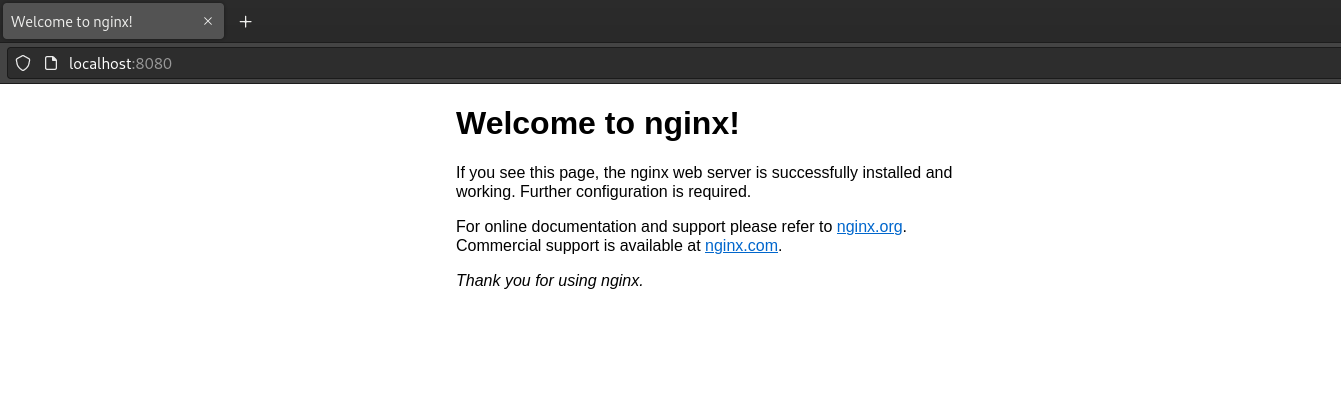

Then, you go to localhost:8080 in your browser, you will see this:

If you were curious and looked at my Docker Cheatsheet, then you would know that the first docker command pulls the nginx image from DockerHub. The second command runs the latest version of a nginx container in the background and points port 80 FROM the nginx container TO port 8080 on your machine.

You can check the installed images by running

docker images

Output:

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

nginx latest b692a91e4e15 6 days ago 142MB

Docker Process and Format

Next, copy this alias into your bashrc if you run bash or your zshrc for zsh:

alias dps='docker ps --format="ID\t{{.ID}}\nNAME\t{{.Names}}\nIMAGE\t{{.Image}}\nPORTS\t{{.Ports}}\nCOMMAND\t{{.Command}}\nCREATED\t{{.CreatedAt}}\nSTATUS\t{{.Status}}\n"'

What this does is format the output of the docker ps command so that its more readable. Go ahead and run these commands in your terminal to see the

difference.

docker ps

dps

Output:

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

0cf13de873ae nginx:latest "/docker-entrypoint.…" 2 hours ago Up 9 seconds 0.0.0.0:8080->80/tcp, :::8080->80/tcp thirsty_montalcini

---

ID 0cf13de873ae

NAME thirsty_montalcini

IMAGE nginx:latest

PORTS 0.0.0.0:8080->80/tcp, :::8080->80/tcp

COMMAND "/docker-entrypoint.…"

CREATED 2022-08-08 15:11:45 -0500 CDT

STATUS Up 20 seconds

Docker Names

As you can see from either of the previous commands, our container can be identified from either its ID or its name. This is very useful for starting or stopping that container or even checking its logs. However, its name is kind of hard to remember as its randomly generated. We can thankfully create an easier to remember name for our containers. To do this, first lets stop the current running container.

docker stop thirsty_montalcini

Next, lets create a new container with a name of mysite:

docker run --name mysite -d -p 8080:80 nginx:latest

Finally, run dps to check the name

dps

---

ID 9436589ac4c4

NAME mysite

IMAGE nginx:latest

PORTS 0.0.0.0:8080->80/tcp, :::8080->80/tcp

COMMAND "/docker-entrypoint.…"

CREATED 2022-08-08 17:48:09 -0500 CDT

STATUS Up 2 seconds

Docker Ports

Even though we brushed over ports with docker, lets go over some commands that include it. To recap, the -p flag of the docker run command

requires a “destination” port and an “source” port in the form of DESTINATION:SOURCE. You can also use more than one port in a container. To

test this lets run nginx on port 3000 and 4000:

docker run --name multiport -d -p 3000:80 -p 4000:80 nginx:latest

Next, run dps to check the ports on the container.

ID 31875b1e2d0f

NAME multiport

IMAGE nginx:latest

PORTS 0.0.0.0:3000->80/tcp, 0.0.0.0:4000->80/tcp, :::3000->80/tcp, :::4000->80/tcp

COMMAND "/docker-entrypoint.…"

CREATED 2022-08-08 21:32:38 -0500 CDT

STATUS Up 4 seconds

Finally, check localhost:3000 and localhost:4000 in your browser. You should see the nginx welcome page on both tabs

Docker Management

There are a few commands that make managing docker images and containers easier such as how to remove containers, how to get an interactive terminal, and how to list containers.

Listing containers

docker container ls

Interactive Terminal

docker exec -it multiport sh

Remove a Container

docker rm multiport

Remove a Running Container

docker rm -f multiport

Docker Volumes

With Docker Volumes, you can share files and folders from your host machine or docker container to another docker container.

Between host and container

docker run --name website -v $(pwd):/usr/share/nginx/html:ro -d -p 8080:80 nginx

In this command, the -v flag is used to take the files and folders from the current directory and place them inside the nginx

docker container at /usr/share/nginx/html in a read-only or ro state.

Between container and container

docker run --name website-copy --volumes-from website -d -p 8081:80 nginx

In this command, the --volumes-from flag mounts volumes from the specified container, in this case website, to the docker the called it,

i.e. website-copy.

Advanced Docker

Now that we’ve gotten past the basics of Docker, lets move on to the more advanced subject of image creation. This will include information about:

- Dockerfiles or how to write your own images

- Caching and Layering, how writing your Dockerfile a certain way can effect your image

- Alpine Linux, a way to slim down your image to an extremely small size

Dockerfile

With a Dockerfile you can create your own template, defining how you would like your environment to be setup exactly for you application to run. A Dockerfile can also be used as a snapshot tool, so if an error is made with a newly create image, you could roll back to the previous version with little issue. Please note that this post is not all encompassing and will not show every command you can use in a Dockerfile. For that I recommend that you check out the Dockerfile Reference.

To get started, lets create a directory and add a basic html template file inside.

mkdir dockerfile-test

cd dockerfile-test

touch index.html

index.html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Page Title</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is a Heading</h1>

<p>This is a paragraph.</p>

</body>

</html>

Next, lets create a Dockerfile. With your favorite text editor add this information inside of it and save it as Dockerfile. Make sure there are

no file extensions at the end.

Dockerfile

FROM nginx:alpine

ADD . /usr/share/nginx/html

To break this down, Dockerfiles are written with an instruction which are in all caps and a value which are lower-cased for the most part. In this

Dockerfile the FROM instruction states what docker image (i.e. nginx) and tag (alpine) to use when building the template. The next line uses

the ADD instruction to add the files from the current working directory to the /usr/share/nginx/html directory inside the template.

To turn this Dockerfile into a docker image, you need to build it. You do so by running:

docker build -t myimage:alpine .

This will build the image myimage and tag it as alpine.

If by any chance there are files or folders that you do not want inside the template, simply create a .dockerignore file in the same directory

and add the names of the files and folder you do not want copied. For example, lets say you initialize a git repo inside of the dockerfile-test directory.

You probably don’t want a copy of the .git directory or .gitignore file inside of your image. Simply create the .dockerignore file and add:

.dockerignore

.git

.gitignore

Docker Caching/Layering

Docker Caching is the process of storing information so that it can be reused for future events.

Docker Layering is the technique of using cache to create small, fast docker images

For example, lets say you are building a nodeJS project and need to build an image. You write your Dockerfile as so:

FROM node:latest

WORKDIR /app

ADD . .

RUN npm install

CMD node index.js

However, since you have a lot of dependencies, your container takes a long time to build. This is because this Dockerfile is not fully taking advantage of caching. On line 4 of the Dockerfile, the image has to always re-download all of the dependencies your application would need to run. This is very inefficient and time consuming.

To change this, you should know where node stores information regarding dependencies, in

this case any of the package.json files. Let’s go ahead and add those lines above the ADD instruction:

FROM node:latest

WORKDIR /app

ADD package*.json ./

RUN npm install

ADD . .

CMD node index.js

Now rerun the build command:

docker build .

You should see an increase in speed the next time you build your image!

Alpine Linux

Docker images based off of Alpine Linux are usually much smaller in size compared to their vanilla counterparts. To get Alpine as your docker image, first you have to see if the alpine tag is supported under your specific docker image. Take for example nginx. If you search nginx on hub.docker.com you will see under the nginx image page a bunch of tags related to different nginx versions as well as Linux distros. Look for a tag with alpine in the name. To download it onto your local machine run:

docker pull nginx:[tag you want to use]

For me, I just usually go with the simple alpine tag.

docker pull nginx:alpine

Now compare the image sizes by running

docker images

Wrapping it up

Wow, that was a lot of data in one post. You went from just starting and stopping an image to building a fully functioning Dockerfile and image

of your own. Congrats 🎉!! Now go outside and touch some grass, I know I need too 😄. If you like this style of content, please feel free to look at

other posts in the Explained category.